My history’s a little rusty, but even I know that a French aristocrat travelling into the centre of the French revolution isn’t the smartest plan ever devised. But I’m diving right in at the end of the instalment. The beginning has time flying again – the pacing of the story is rather stop-start isn‘t it? Another three years have gone by, and this time they’re thrown away in a line rather than the echoes of footsteps giving us information on deceased children along the way. The revolution is in full force by now, and after all the build up we can perhaps appreciate Dickens’s surprise at the aristocrats who never saw it coming – of course, the build up we have been experiencing is a condition of hindsight where the end has already occurred, and it is with that hindsight that Dickens perhaps treats the aristocracy unfairly in presuming them well-versed in foretelling their future. I particularly enjoyed the reference, when likening the aristocracy’s provocation of the mob to devil worship, to reading the lord prayer’s backwards – so that’s what they did before the Beatles started making records.

I was also intrigued by the continuing reduction of the aristocracy in Dickens’s narrative to the singular title/persona of Monseigneur. It has a dual effect: on the one hand it reinforces the anonymity of each nobleman and is therefore dismissive of their individuality, suggesting that who they are as a person is irrelevant to what they have done – or rather not done, en masse; a particularly significant judgment compared to Darnay‘s own beliefs that he will not be in danger from the mob because of his previous fairness and qualities as an individual. On the other hand, continuing to resurrect Monseigneur as a title for a multitude of characters is suggestive of the immortality of the class – kill one and another will take its place, a hierarchical hydra that shows the limit and futility of the fury and rage sweeping through Paris.

There are more doppelgangers and dual identities this week in Darnay and the Marquis St Evremond. Just as Dr Manette talked about himself in the third person, so too does Darnay try to justify himself from an outside perspective rather than coming to terms with himself. The idea that Darnay and the Marquis are two separate entities, their boundaries defined by the English Channel, results in a loss of self-awareness, further underlined by Darnay’s naïve optimism about the success and security of his trip abroad.

However, one simplification this week is that there are no longer any misconceptions about Stryver, whereas in his early appearances he maintained two personas as a great barrister and a ruthless manipulator resting on the laurels of Carton, now his hypocrisies and more odious characteristics are obvious to the central characters; interestingly this coincides with their greater appreciation of Carton’s true potential and worth; to know the one is to know the other.

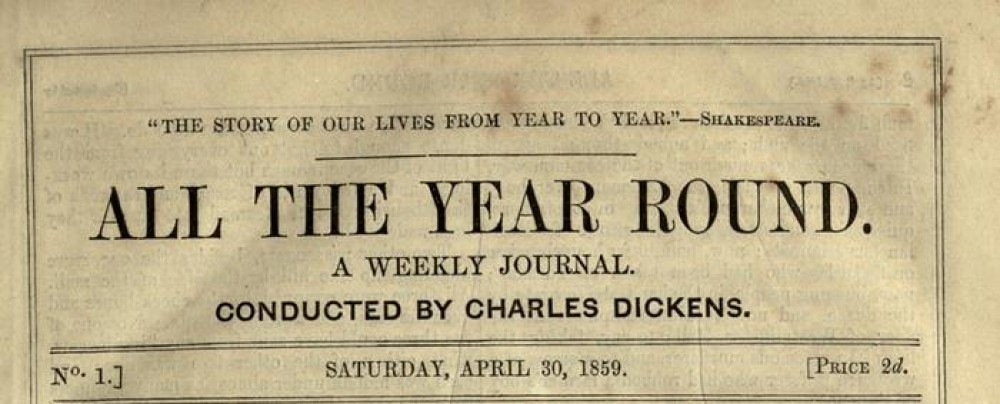

It’s a shame that in arranging the contributions to this week’s edition that Dickens didn’t place “The Future” immediately after ATOTC as the ponderous, half-morbid, half-hopeful forecasting within fits in nicely with the tone of Darnay’s own musings over the fate awaiting him abroad and in book three. Instead, the instalment is followed by “North Italian Character” with its rather jarring, Stryver-like judgements early on that “The French never do so well as when their vessel of state is steered by a firm, a capable, and even a severe pilot”.

Well it’s 31 May, which, as the advertisements on the back page of ATYR have been telling us, means the first monthly volume of ATOTC would be available today. This offered any latecomers to the journal the opportunity to catch up with the previous instalments, as well as giving them time to pick up this week’s copy of ATYR and carry on reading! However it’s equally likely that readers of the weekly and monthly parts were distinct from one another – the publication of ATOTC in both formats was a gamble that didn’t quite pay off, with sales of the monthly volume proving disappointing, presumably because everyone was reading it in ATYR first.

Well it’s 31 May, which, as the advertisements on the back page of ATYR have been telling us, means the first monthly volume of ATOTC would be available today. This offered any latecomers to the journal the opportunity to catch up with the previous instalments, as well as giving them time to pick up this week’s copy of ATYR and carry on reading! However it’s equally likely that readers of the weekly and monthly parts were distinct from one another – the publication of ATOTC in both formats was a gamble that didn’t quite pay off, with sales of the monthly volume proving disappointing, presumably because everyone was reading it in ATYR first.