Apologies for posting this so late in the day. Events in life are occasionally as contorted as in the story.

It has been a long journey. Hung up my coat, cleaned off my boots and indulged in a tall, china mug of tea. All that is left is sit by the fire and contemplate where I have been and why.

The why is easy, besides having done a bit of work for DJO it had been more than sixty odd years since I had last travelled the mud covered roads from London to Paris and back again. And what an exciting road it was, sitting at a long polished oak table in the Co-op library above the Co-op grocer or trudging the roads of North Durham.

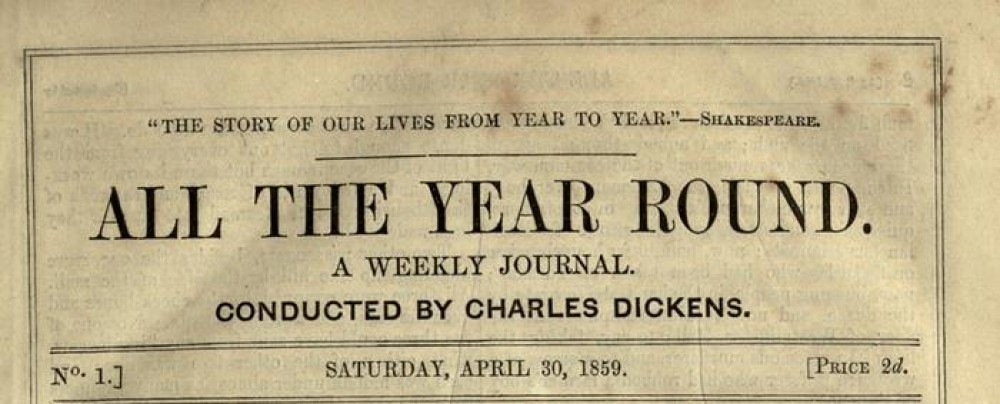

I don’t suppose a year has passed since then when I haven’t heard someone quote both opening and closing lines from the Tale so reading the whole story again in its original serial form was a challenge I could not resist.

The journey itself was not quite how I had imagined it. Riding the mail down to Dover was as disconcerting as it had been, with the sight of Jerry muffled up in thick woollen scarf and riding cape (not the cringing wimp in the Phiz illustration, more of a Robert Newton on a bad day in Hatter’s Castle) making my heart stop as he appeared out of the fog and the mad dreams punctuated by ruts in the road giving me nightmares when I fell asleep.

Guts turning over at the wine shop scene, sadness and anger as an old man made shoes. Edge of the seat when young Jerry was chased by coffins (I avoided walking through the cemetery for two weeks after that, even though it added a long walk around the village to get to school) Some lovey-dovey stuff then the thrill of the Bastille. As for the rest; a determined French woman crying vengeance, a kangaroo court, prison, escape and Carton. He was a hero at a time when there had been lots of heroes in the war like the young DLI rifleman who, despite having parts of him missing, carried on firing a two pound gun so that his mates could make a safe retreat.

The closing lines have always struck me as something of an epitaph for those who had made such a sacrifice.

Getting back to the subject, the book I have just read is not the same book I read sitting on a hard wooden chair. Nothing in the words has changed, nothing in the writing has changed but the meaning has changed radically. Over the first fifteen weeks I was content to renew acquaintance with half forgotten characters such as Miss Pross, the Vengeance, Jerry and more, whose names, and sometimes roles, had long slipped through the sieve of my memory. The discipline of ‘not knowing‘ what came next in the story was frustrating at times but provided the same opportunity for discussion and reflection on ‘the story so far’ as its Victorian readers had and digging into more detail than a straight reading would allow for. There were times however when blogs and comments tended to indulge in the mediaeval ecclesiastic sport of counting how many angels were dancing on the head of a pin and I was happy to take part in the game. However at week sixteen I sensed that something was not quite as it should have been and by week twenty I had so many nits chewing at me that I knew that I was not on the same wavelength as others and I didn’t know why.

A more leisurely re-reading of the parts that had left queries in my head lead me to the first of several breadcrumb trails Dickens had left inside the story.

It is this point I should confess, I did not read from the DJO site but from the Penguin 1994 edition which is conveniently divided up in sections as per the weekly instalments. Reading from the transcription is awkward for me as with the short lines I find myself reading in a cross between blank verse and a nursery rhyme. This time I checked the facsimile pages which don’t bother me so much.

Had I been using the transcript, I may have picked up on this earlier because someone else somewhere in the past had queried two sentences. These are on page four of the facsimile. When reading from the transcription the first column of the facsimile is visible and one line has been marked in pencil. When the page is expanded to full size immediately beside the marked section, which records Jerry’s thoughts as he watches the mail get underway, there is another mention, almost a repetition, of what he is thinking as he rides back to the bank.

Whether the pencil marks were made by some student following through the original text, God forbid, or possibly by the first owner of the volume also queried it, I would like to think so, doesn’t really matter. What is important is that it brought me up short and I knew I had walked into one of those sleights of literary magic Dickens throws out in his stories, misdirecting attention from what is actually going on to something different

When I first read these I dismissed them as being the thoughts of a working man wondering what would happen to him, and his wages, if indeed the dead were recalled to life and the labour market became over saturated. As it is these are the beginnings of the line of crumbs leading through Mrs Crunchers head being banged on a wall, Jerry sucking rust from his fingers and Mr Lorry’s comment about graves to the “The Honest Tradesman” where his Resurrection business is revealed

From there I have followed several breadcrumb trails which have changed the whole story for me.

Where once Lucie was a boring, weepy girl I see her know as a strong character directing and supporting three strange men to the extent of spending hours a day for more than a year standing outside a prison wall to bring comfort to the man she loves. If Leander could swim the Hellespont and Penelope unpick her tapestry why is Lucie waiting outside La Force a silly idea?

Mr Lorry is no longer a genial old buffer who bounces around the story. He is a man of secrets who once fell in love with a woman he could never marry but found happiness as an adopted member of her daughter’s family.

As for Carton he is nothing like the DLI Rifleman. A talented man who can’t cope with his own history and wastes himself in drink and self pity and eventually finds a way to commit suicide without carrying the stigma of what was then a crime.

Those famous last words belong to Dickens, not Carton, as he ruminates on the recent events in his life.

Whilst most of the writing is fine I now find the story is trite and not the old adventure I loved. My copy will go back on its shelf and I don’t think I will be tempted to read it again.