And so on to the penultimate part. I was watching the new series of The Killing on Saturday and I always love the montage sequence at the end of every episode, showing the key characters in telling scenes. This entire instalment is a little like that, although it’s a montage we must construct in our mind. Thus, Sidney is still clasping the hand of the seamstress, awaiting the tumbrils; Charles is still unconscious; and Lucie and Mr Lorry still peer fearfully from the carriage window as it races through the French countryside. Remarkably, given last’s week emotionally charged instalment, and given that this is the penultimate part, these major characters remain firmly out of sight.

I was struck this week by how brilliantly Dickens depicts the paranoia, fear and murderous rage of the Revolution. Given our recent discussions about plot, it is interesting to consider one of the word’s other meanings – namely, a plan made in secret by an individual or group to do something wrong, harmful or illegal – as Paris has become a city of plots in which Lucie’s harmless gestures outside the prison become dangerously freighted with political meaning. I was reminded of the paranoia and terror of a fascist or totalitarian society, in which ‘wrong’ words, deeds or even thoughts are enough to bring death. The Revolution has truly become a devouring monster, with death pursued only for its own sake and for the spectacle it brings. Thus, Jacques 3 wants to send Lucie Jnr. to the guillotine because ‘“we seldom have a child there. It is a pretty sight!”’ It feels to me that, as in Barnaby Rudge, death and perversity are interlinked, with death itself becoming a source of erotic fascination and pleasure.

If last week was about the struggles of the ‘goodies’, this week we’re back to their Manichean opposites. I love the homosocial relationship between Madame Defarge and The Vengeance in this instalment. Defarge places her fingers on The Vengeance’s lips, while The Vengeance calls Defarge ‘my cherished’ and ‘my soul’, embraces her and kisses her cheek. MD possesses a magnetic, sexualised force of attraction – people desire and fear her simultaneously. She is, thus, the pure embodiment of the Revolution: bloodthirsty, vengeful, paranoid, devouring – and disturbingly sexy. Dickens amusingly remarks of Madame Defarge’s dress, ‘it was a becoming robe enough, in a certain weird way’, as if he can’t quite acknowledge that this ‘monster’ is sexually attractive. Barbara Black has written convincingly of Madame Defarge as a figure of fear and sexual attraction, distracting both Dickens and the reader. It strikes me that Madame Defarge is, in some ways, similar to Miss Wade in Little Dorrit: both are beautiful, clever, determined and relentless; and both have been powerfully misshapen by earlier experiences. Both also enjoy strong social and erotic bonds with other women who worship them.

This instalment is wonderfully cinematic as we cut between the comic scene between Jerry and Miss Pross (which, truth be told, didn’t make me laugh once) and the relentless progress of Madame Defarge, almost animal-like as she tracks down her prey. Jerry is unconvincingly redeemed by the softening influence of Lucie – he will give up grave digging and allow Mrs Cruncher to ‘flop’. I think I preferred him before.

And then ding ding, final round! Miss Pross versus Madame Defarge – Great Britain versus France – love versus hate. The scene is brilliantly set up, with Miss Pross, half-blinded after washing her face, suddenly confronted by the phantasmal figure of Madame Defarge. It struck me that this scene, with the two women growling in their respective languages, might seem a little silly if enacted, but it works wonderfully well on the page. I’m not quite sure how I feel about the demise of Madame Defarge. Personally, I find it a little anti-climactic and, although ‘the soul of the furious woman’ is forcibly separated from her body with a (deafening) bang, it feels more like a whimper to me. And what do we make of the resulting deafness of Miss Pross – is it rich with some symbolic or moral meaning I can’t quite decipher, or did Dickens just like the idea?

And for those of you interested in queer readings of Dickens: the struggle between the two women, in which Miss Pross seizes Madame Defarge ‘round the waist in both her arms, and held her tight. It was in vain for Madame Defarge to struggle and to strike’, reminded me of the to-the-death struggle of Rogue Riderhood and Bradley Headstone that comes in 1865 in Our Mutual Friend. This scene has been the subject of many queer analyses and much discussion about anality and whether homosocial relations in Dickens are violent and phobic. It’s fascinating to place the two scenes side-by-side and consider if this earlier, all-female version impacts on our reading of OMF.

I agree about the sexualized portrait of Madame Defarge, creating both erotic attraction and fear in equal measure. She contrasts with Miss Pross who is virtually desexualized (‘ the years had not tamed the wildness, or softened the grimness’ …‘she saw a tight, hard, wiry woman before her’ ) Surely Madame Defarge’s erotic attraction is lost on Miss Pross, who sees only a force to be fought against to the death to protect her ‘ladybird’? The notes in my World’s Classics paperback suggest that Dickens had Lady Macbeth in mind as he developed Madame D, identifying her husband’s ‘weakness’, his loyalty to Dr Manette, and presenting her as a creature totally without pity. I don’t think I would have made the connection, though, without that prompt.

There is a letter from Dickens to Bulwer Lytton in which he justifies the manner of Madame Defarge’s death – an accident, brought about by the ‘half-comic intervention’ of Miss Pross, saying that he wanted her to have a ‘mean’ death, ‘instead of a desperate one in the streets which she wouldn’t have minded’.

I’m really intrigued that Dickens wanted, in some sense, to ‘punish’ Madame Defarge with a mundane death. There’s a chilling moment in this instalment in which Dickens says that she would have gone to the guillotine without fear, but it’s clear that her creator wanted to deprive her of the dramatic, self-aggrandising death she courts throughout the scenes of revolutionary violence. Like the self-immolating rioters in Barnaby Rudge, Madame Defarge is so perversely enamoured of death that even her own demise becomes appealing. Dickens talks of Madame Defarge as his character, under his novelistic jurisdiction, yet somehow alive and independent. We know that he publicly praised Shakespeare’s characters as universal, eternal and independent of their texts (hence the Lady Macbeth comparison, perhaps), so perhaps he felt the same towards his own creations here.

If I were a Victorian reader, this week’s installment would have had me screaming, “Enough of Madame Defarge! Get back to Sydney!” Kind of like a cliffhanger on TV, as we were saying earlier.

I was also intrigued by the structuring of this week and last. I’d forgotten Dickens had arranged it this way, so was somewhat confused last week to read of everyone driving off to safety, and wondering where Madame and Miss Pross’s bout was going to fit in. What Dickens has done is decide to split his story up by character and incident rather than through basic narrative chronology (not for the first time – we’ve already gone back in time for Manette’s letter). Had he tried to tell it all in real time, then we’d presumably have had Carton and Darnay swapping places last week, followed by Madame and her cronies meeting, then this week we would have had Carton meeting the samstress, Madame and Miss Pross meeting up, and everyone else escaping. I much prefer it that Dickens gets all the rest out of the way last week to give Miss Pross the spotlight she deserves (incidentally, can anyone at this point spot who my favourite character in the story is?)

Ah, it’s mission improssible.

This is one of my favourite moments in Dickens’s work. Don’t ask me why, but I am genuinely moved by the actions and feelings of Miss Pross in this chapter. Sometimes the most poignant moments come from otherwise comic characters being allowed the opportunity to be taken seriously (Dickens made a similar comment justifying what others perceived to be the change in character of Pickwick from comic buffoon to kind-hearted philanthropist, arguing that our first impressions notice only the oddities of a character, voerlooking their humanity beneath). It’s also placing the entirely domestic into a scene of violence and conflict, of reinforcing the ordinaryness of a protagonist in a hellish situation (this has been done in numerous war movies, also I’m reminded of Samwise Gamgee in Lord of the Rings) we are told that ‘Miss Pross had nothing beautiful about her’, before seeing the beauty of her absolute devotion to the child she has raised as her own. If the death is demeaning to Madame, it is the making of Miss Pross.

We’ve talked in the past about Lucie and Madame being polar opposites, but now it turns out Dickens has hoowdinked us and brings out Madame’s real nemesis from the shadows. Madame ‘knew full well that Miss Pross was the family’s devoted friend; Miss Pross knew full well that Madame Defarge was the family’s malevolent enemy.’ It’s a fantastic twist – Lucie has dominated the story for so long that you would expect a showdown between her and madame, so to make Miss Pross the unassuming hero only increases the impact of the moment.

Their polar opposition continues in their speaking different languages to one another, and while Miss Pross recognises Madame as hell personified, Madame continues to disregard her opponent’s humanity as a strength. Dickens calls Madame Defarge a tigress (echoes of Shakespeare’s description of Queen Margaret as ‘tiger’s heart wrapped in a woman’s hide), devoid of pity, and she the emotions of Miss Pross are a “courage that Madame Defarge so little comprehended as to mistake for weakness.” Thus Miss Pross’s tears are seen as a failing, and Madame refers to her as an imbecile, calling out for the Manette’s instead: Miss Pross is a woman of no significance, and it is this overlooking of the common person that is her downfall – an ironic conclusion to a champion of the revolution. She has become the very tyrant she sought to overthrow. She has taken everything to extremes – she would not mind even her own death if it were ordered for the revolution’s cause – and as a walking symbol of the revolution she has lost her humanity, so that ultimately it is humanity itself which is the only way to effectively kill her off. She is not killed in action, or revenge, or loathing, but killed through the act of selfless love and protection as Miss Pross, ‘who had never struck

a blow in her life’, uses all her strength and riskes her own life just to give Lucie time to get away.

There is a danger here that in defeating Madame, Miss Pross could be doomed to follow in her path, but Dickens is careful to show this will not be the case – throughout the struggle she maintains thoughts of love and protection, not hate or revenge, and she leaves the event scarred, deaf for life, haunted forever by that final sound of the gun.

Now if you’ll excuse me, I’ll be in the corner weeping hysterically.

I know she’s the arch villainess, but I’m a bit choked by the death of MD. It’s great to have a Dickensian woman who stalks the Paris streets armed to the teeth ‘with the supple freedom of a woman who had habitually walked in her girlhood, bare-foot and bare-legged, on the brown sea sand.’ I’ll miss her. But credit to Pross power for seeing off this formidable enemy. Hope you’re a bit recovered Pete.

I’m a little better now for a strong cup of tea, thanks Holly – gearing up now for the final instalment (may need to bring a hipflask to work for that one).

That was a wonderful analysis!

Interesting points Ben about erotics of violence. Madame Defarge seems to echo the voracious, sometimes homoerotic, enthusiasm popularly attributed to the Guillotine as thirsty, ‘sharp female’. Back at the start of October we had this description, in which La Guillotine is set to drink up ‘lovely girls’, amongst others:

Lovely girls; bright women, brown-haired, black-haired, and grey; youths; stalwart men and old; gentle born and peasant born; all red wine for La Guillotine, all daily brought into light from the dark cellars of the loathsome prisons, and carried to her through the streets to slake her devouring thirst.

I’m intrigued by the comparison with Miss Wade, but I think there’s a problem of emphasis with this kind of reading, as those who are mad, bad, and dangerous to know become most legible as having same-sex desires, as if their perversity of various kinds allows us to read them in this way. While Dickens clearly does represent homoeros of a gentler variety elsewhere in his fiction (I’m thinking, as those of you who’ve worked with me will predict!, of his accounts of male intimacy via nursing that structure Great Expectations for example) it seems that there is less space for this within the violent tumult of his historical fiction. Ben and I have been having a discussion about whether there are any more reparative forms of queerness in Barnaby Rudge – it would be great to have other ideas about this! – but it seems that in both ToTC and BR more gentle homoerotics are in short supply.

As we’re nearing the end of this epic journey I’d like to raise the question of the complex emotional and erotic attachments that Carton has to the Darnay family. In an earlier post Ben raised Sedgwick’s classic account of rivalrous triangles, in which rivalry between men for a woman they both love is just as much about the attachment between the two men. What I find fascinating about the version of this structure in TofTC is the way that it is worked out as the ultimate sacrifice, so that rivalry over a woman, which often gets worked out in other Dickens novels in violent encounters between two men – notably Eugene Wrayburn and Bradley Headstone in Our Mutual Friend – is rerouted into an act which (we hope will) preserve the man loved by Lucy and by Carton. I’d be very interested to hear any other thoughts on this.

There’s another Lucie involved in this triangle of course, and it’s interesting to me how Dickens writes that both she and her ill-fated brother are taken with Carton – so he is not only a potential rival to Darnay as a husband, but as a father as well. So the final conflict between Carton and Darnay is not of destruction, but of preservation – who will do the honourable thing and die for their family? Of course you can bring in the pseudo-autobigroaphy at this point to explain why Dickens would be so interested in a love rival having the approval of the kids, although I’m not aware of Ellen Ternan ever spending any qualitiy time with Dickens’s children – or if you were felling particularly gossipy you could argue that in depicting an ousted love rival wiling to lay down and die that he is projecting his hopes for how Catherine will react to Ellen’s arrival in his life!

I have to confess to not being convinced about homoerotic sensations in the showdown between Pross and Defarge (which is sounding more and more like a boxing match each time we talk about it) – but if you were to look at it in that context, then the description of Miss Pross as specifically not beautiful is intriguing – does her lack of sexuality also identiofy her as the antithesis to Madame? In an earlier illustration on the blog where Phiz depicted Barsad chatting to the Defrages, both Ben and I noted that Madame was not as we had imagined her; sher always seems somewhat crone-like in the text, while the illustration shows her as a typical young damsel, not so far removed from a heroine. If we’re re-imagining Madame as a dangerous beauty, is she not more closely related to the yet-to-be-written Estella? Dead to feelings, committed to the cause, scornful of tears…

I’m not convinced about them either. Mme is a cold claulating woman with a single agenda, to rid the Republic of all traces of the nobility and the Evremonde name especially. To this end she may well allow small intimacies from her followers but as soon as their usefulness is over she shrugs them off like so much dross. She has given up on Defarge, he opened the Bastille, found the incriminating letter, his job is done and he is cast aside. She holds her small court in contempt though they do worship her but she would happily send them all to the guillotine at the drop of hat once they have done as she wants. As such a character she represents the terror par excellence. Once the enemy has been destroyed the guillotine will turn in on itself and consume those who have fed it.

Miss Pross however was born on an island, why shoud she cross salt sea. A loyal monarchist (English that is) she will defend her own no matter what it takes. She may appear to be a simpering female to Mme but underneath that velvet glove there is a solid iron fist.

Having dispatched the threat, she goes home with a metaphorical bloody nose and settles down to supply her ‘family’ with copious lashing of ‘Rosbif.’

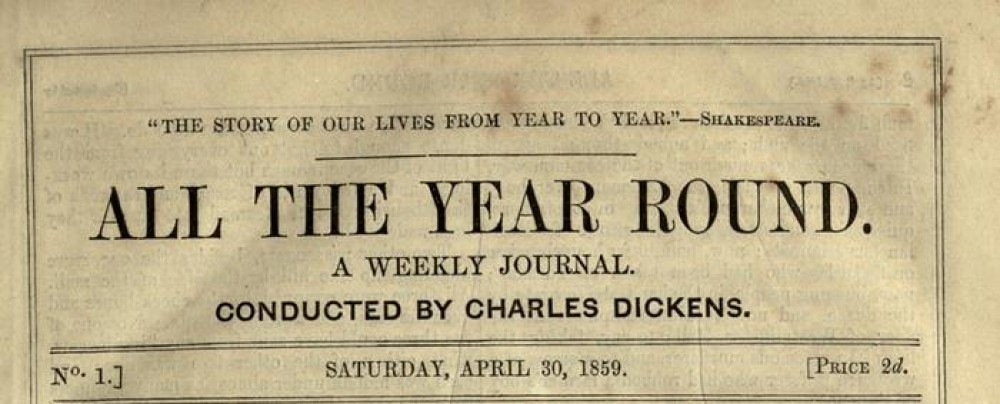

This is a really wonderful reading of Madame Defarge, Mr Booley. I was thinking that many Victorian readers of AYR would probably have been aware that the Terror did, indeed, devour its own children, with Danton and Robespierre, among many others, ending their days on the scaffold. Can we perhaps surmise that MD herself would have been devoured by the National Barber as the Terror reached its apogee? I was wondering if MD’s ferocious lack of humanity is what makes her an object of (erotic?) fascination for others. Perhaps, for the The Vengeance, fear is aa important an element in her worship of MD as desire.

I’m really enjoying this discussion about the queer possibilities for later readers. To pick up on Rokojulady’s very valid points about the cultural acceptability of highly emotive romantic friendship between women in the period, I just wanted to add that I think the blurred line between the physicality of a romantic friendship, seen by Longfellow as ‘a preparation in girlhood for the great drama [ie marriage] of a woman’s life’, and erotic relationships makes for an important space in Victorian fiction. Sharon Marcus’s work is brilliant on this, as is Lisa Moore’s. I’ve been thinking about how some of Dickens’s first readers, like Emily Dickinson, used his presentation of intense friendships between women to think through their own friendships. Later on Dickens’s work is used explicitly in love letters between women, eg. by Katherine Mansfield.

I’m now trawling the internet for carton/darnay fanfic! Dirk Bogarde’s wonderfully tight trousered performance of Carton has an important part in this legacy I think.

I’m not sure I’d describe Carton’s relationship to the Darnays as having an erotic undertone. I’m also not sure there’s anything erotic between Carton and Darnay (although I think if you look on fanfic.net, you can find some pieces that that “explore” that angle….) I never got the impression that Carton and Darnay were anything but platonic, and even that, mainly because of Carton’s affection for Lucie. It’s pointed out that Darnay doesn’t spare a thought for Carton in his own will which is kind of sad. I Think one of the most disturbing parts of the last few chapters, at least as pertains to the love story is that in the rush of escape and Cruncher/Pross’ discussions, no one seems to spare a thought of him.

Also, I think when exploring the queer angle of the relationship between Defarge and Pross it’s useful to define queer. I suspect that it took a whole lot more affection between women to be homoerotic in Dickens’ time and in the late eighteenth century than we would require today to label an interaction as ‘queer’. In fact, in a time when many marriages were not love matches and a woman’s place really was in the home with the kids, there was a lot more seperation between women and men. One would expect that a woman’s relationship with another woman would be far more intense than it would be to any male that she knew, just because she was expected to stay in the company of other women–because they could relate to each other better. In this light, the embracing and kissing between Defarge and the Vengeance doesn’t so much have a lesbian connotation as one of intense friendship which would not have been viewed as erotic by either Dickens’ society or that of the Revolution.

However, I think that comparisons that the author may never have intended are useful for the viewer in what they take away from the art and how they incorporate the art into their lives. In this respect, a query interpretation of Madame Defarge might be very poignant.

Thanks for this really interesting post, Rokujolady. I must check out this erotic fan fiction — it sounds like great fun! That’s very true about how easily Sidney is forgotten by the fleeing family, which I suppose we could attribute to the confusion and terror of escape, but nonetheless, it’s harsh.

You make a very good point about the erotics of same-sex friendship. There has been much intense discussion within lesbian scholarship about whether friendships and loving but (apparently) non-sexual relationships between women were ‘lesbian’, or ‘queer’, or a different category altogether. It’s a fascinating debate, albeit one that will roll on and on simply because we don’t know where the boundary between friendship/eroticism can be found in many of these relationships — and it will vary greatly, too. While I agree that, perhaps, Dickens and some of his readers may not have viewed the kiss between MD and The Vengeance as erotic (although I think we should tread carefully here), I still think we can interpret it as an intriguing moment of queerness. As you say, literature can contain and engender moments and feelings unintended by the author, but profoundly felt by contemporary or later readers.

I suspect the lack of discussion of Carton in this instalment is less about the callousness or thoughtlessness of the others, so much as Dickens directing our focus – we were with Carton last week, we can presume we will hear more next week. At this point in the tale, where everything is being wrapped up and various climaxes are being reached, Dickens is making us focus on the here and now rather than what’s happening around the corner.

I haven’t blogged about the the serialisation for quite a few weeks (though I have still been following your comments, honest) but it occurred to me a while ago that there is something not just melodramatic but operatic about some of the scenes in this novel – for instance one can imagine a Verdi-style soprano aria for Lucie as she waits outside the prison (chapter 5 of part III), with perhaps an accompaniment of “la, la, la”s from the (bass?) wood-sawyer. Here in ch 14, too, the dialogue between Mme Defarge and Miss Pross – each in their own language – could easily be an operatic duet, with each participant singing her own theme against the other. Is there something about mid-nineteenth-century European culture that would suggest Dickens and Verdi (born 1813) shared something of the same sensibility?

I agree that this chapter ends splendidly – better than it starts, where once again the two-dimensional Vengeance, Jacques Three et al are only tolerable – and I liked Pete’s point, a propos Miss Pross, about Dickens sometimes allowing comic characters to be taken seriously (CD should have done it more often – often his comic characters seem trapped in their one-dimensional mannerisms). I looked back to the novel’s introduction of Miss Pross in Part I and was agreeably surprised to see how CD seems to have prepared us for this fight: straight away in ch 4 we are told of her prowess as she lays a “brawny hand” on Lorry, sending him “flying back against the nearest wall”, and is referred to as “the strong woman”. Red hair of course is a Celtic trait, and Pross is a Welsh name: did Dickens see the Welsh as especially pugnacious?

Thanks for these wonderful observations, John, which have certainly given me a lot of food for thought. I’m not a great opera fan, I must confess, so I’d missed the presence of operatic elements in the text, but I think you’re spot on that they’re there. I started thinking about Les Miserable (the musical, not the book!) — a globally successful musical with similar themes to TOTC (poverty, revolution, thwarted love, self-sacrifice for the loved one, revenge, the law…). It’s fascinating how historical events were being rewritten in the nineteenth century via historical fiction, theatre and opera. I suppose that opera and melodrama both had their origins on the Continent and developed from a culture of Romanticism that emphasised feeling over rationality. Both forms, I think, emphasise gesture and bodily presentation over dialogue: Lucie’s prison visit could easily be enacted without words in either theatrical or operatic form, as you point out.

I had also missed the foreshadowing you highlight here, with Miss Pross’s strength clearly emphasised — and very early on. It seems clear that here was one element of the plot that Dickens had in his mind almost from the outset. I love the idea of Miss Pross as a Welsh warrior!

Nice to hear from you again John! I think opera certainly ties in to the theatrical tendencies we’ve seen in this book, and perhaps is easier than melodrama in helping us to understand its dramatic effect – melodrama is largely misunderstood or sneered at these days, while opera maintains its popularity despite containing some pretty silly and over-the-top stuff. It also caters for those moments in ATOTC when character suffer the most violent of emotional reactions in a very concentrated period of time. However, thinking of ATOC as a musical has led me to thinking of the murder of the bench in terms of Mickey Mouse in the sorcerer’s apprentice (we see a shadow of the bench, Lorry approaches it with the axe, dramatic music ensues shortly before Pross and Lorry are chased round London by a horde of angry benches making a never-ending supply of shoes).

I was intrigued by your discussion of Pross’s name. I’ve been wondering about the names in ATOTC – Dickens so frequently used bizarre names that evoked characteristics of the person, and I wondered whetehr the introduction of French names in this story might involve interlingual puns and portmanteaus. For example, in Evremonde, the monde is French for world, so we have connotations of every world, or perhaps all the world – a reference to the Marquis’s amount of property, or view of his own importance, or perhaps a list of those he has wronged? – while Manette has previously been discussed for its connotations either of Marionette or a little man. But does anyone have any ideas or theories on what Dickens is trying to suggest with Defarge?

You know, there was an opera for TOTC in the 1950s with the score by Arthur Benjamin. It’s one of those things that seems to have disappeared down the black hole of history, though and I can find very little on it, certainly not any recordings.

Also, I like this so much more than les mis. Maybe because Marius is such a lackwit.

I’d love to find out more about this opera. Please do let us know if you uncover anything new. Opera sounds like a great format for TOTC, as John has so convincingly observed. Also, I love your observation about Marius in Les Mis! The first time I saw Les Mis, I was sitting next to some French people and they giggled all the way through it, even when we were sobbing at the end.

I am so disturbed that these instalments with all these new imaginations will end next week!

Don’t worry too much about the end of this novel. We have plans afoot for a new project, but let’s enjoy the end of this novel first!

Glad you’re enjoying the journey rawanshukur! Forgive me if I’ve missed you before, but are you new to this blog? If so, welcome! We’re quite keen to hear how people who’ve been reading the blog, but perhaps not writing on it, are finding it – I’m hoping that others might take your lead and come in for these last 10 days!

Many Thanks Gail and Holly,

In fact I’m not new to your blog, but before this my comment does not appear in the blog! any way, it does not matter because I still receiving the weekly writings.

It was really a good journey, although it goes too fast, but I enjoy it. It has added many new ideas and explained the story very well.

Thanks to all the participants of this blog and especially to the great efforts of DJO team for making all these installments free!

Essentialy Mme is a centre of power, with out her Vengeance and her followers would have no status in the revolution. Supporting her was the means of ensuring their own continuing existence.

Mme’s power comes not only from persuasion (she has her own cirrcle of knitters whom she visits regularily) but actions like those which she carries out at the Bastille. The problem with actions of that sort is that they have to be continually re-inforced with yet more violence of an increasing inhumanity and the whole struture spirals out of control. The Vengeance I think has reached a state where fear having lead to supplication, producing a reward in terms of increased status and regard enters a simillar spiral where continued habituation leads on to desire and defence of object whatever the cost. Something akin to Stockholm syndrome perhaps?

I would think that had Miss Pross not killed her she would have ended on the scaffold herself. Denounced, for my money, by the Wood Sawyer for whom she has only contempt and abuse.

I love your point about Madame being caught in an ascending spiral of violent acts.

I was thinking about her end, and it occurs to me that actually the worst fate for a character like Madame Defarge would surely be to live – to survive and see through to the end of the revolution. She is a woman of war, someone needed for desperate actions in desperate times, and such a person has no place in a peaceful society (I think Claude Raines says something like this near the end of Lawrence of Arabia). In other words, Madame has died at a time when people like her are both revered and necessary, and she will be mourned. Had she survived, she would have become redundant, shunned and unable to operate in society – she would simply fade away, outliving her usefulness and undoing the power of her reputation by living too long.

ii

Sorry that didn’t work. I’ll try again.