Blimey, month three already? Here are the illustrations that would now be available to Dickens’s readers, and they offer quite different scenes.

“The Stoppage at the Fountain”

“Mr Stryver at Tellson’s Bank”

I’ll confess to not being overly impressed with the illustrations this time round. While the first picture has an impact en masse, the individual characters within it lack detail. The second picture doesn’t quite meet the visual image conjured up by Dickens’s writing of Mr Stryver being too big for the bank – he actually seems rather diminuitive, while the other tellers are far more absorbed in their work than bothered by this boisterous and imposing intruder into their sanctuary.

Though I’m surprised that other scenes weren’t chosen for illustration – the murdered Marquis, for example, or Carton unveiling himself to Lucie, both seem to be more significant moments in this month’s collection – I’m impressed with the two chosen scenes as a pair in so much as the contrast they offer, with tragedy on a national scale in one illustration and comedy on a very personal level in the other, and the way they consequently convey the breadth of ATOTC and the different stories unfolding either side of the channel,

I agree about the forcefulness of the pairing of the two illustrations and also about their comparative crudeness. It is good to have them to hand.

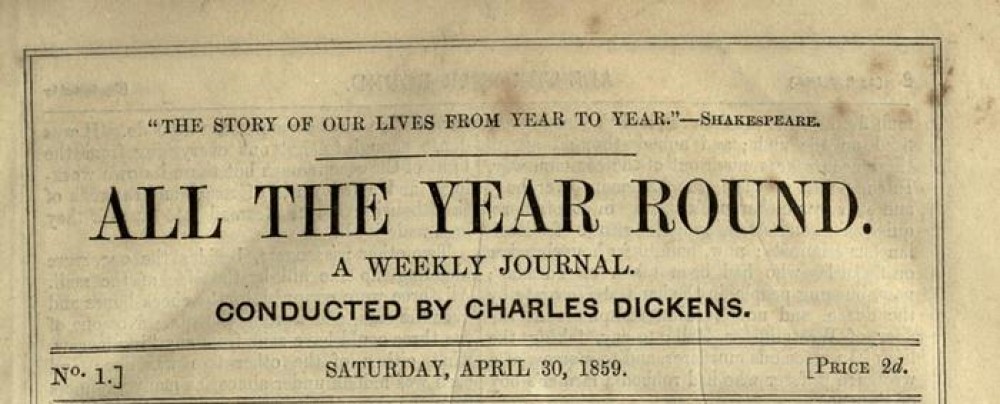

The third monthly number has been advertised in the last two weekly issues . I found myself wondering who the advertisements were aimed at. Surely no weekly purchaser or reader would buy the monthly part, even for the two illustrations?

scrolling back to Pete’s blog on the first monthly part I see that he confirms what I had sensed, that the readers for the weekly and monthly parts were quite separate, and that the monthly parts were a commercial failure. The last two illustrations seem to demonstrate that Phiz is running out of steam .

It does seem a bit of overkill to do weekly, monthly and a final publication, and sends a mixed message that, on the one hand, Dickens’s story is an encouragement for readers to buy his new journal, but on th other hand, you can wait and buy just Dickens’s writing without the interruption of other authors.

I do wonder how widely distributed awareness of the illustrations would have been to readers of the weekly instalments – would they peruse them in the bookstore, or would they have friends who had chosen to buy the monthly instalment? We have come to think of Dickens as a writer whose works have such strong connections with their illustrations that it is odd to think of this story first appearing without any. Does the decision to publish monthly instalments as well as the weekly betray Dickens’s enthusiasm and desire for accompanying pictures that were not practical when writing and publishing on a weekly basis? Should we be viewing these pictures as essential to our enjoyment of the story, or irrelevant and unnecessary?

Having determined to move fiction higher up the agenda for All the Year Round than it had been in Household Words, and to begin the first number with ATOTC Dickens must have been conscious that he would have to sacrifice illustrations in a two penny double columned weekly just as he had done with Hard Times in HW. But in 1859 the popularity of part publication had definitely waned whereas in 1854 it still had a few years to run . Dickens couldn’t have known, in April 1859, that George Smith would launch the Cornhill Magazine under Thackeray’s editorship in January 1860, a shilling monthly that would showcase serial fiction by major novelists, accompanied by illustrations by prominent artists. My guess is that the accompanying monthly parts were a means of keeping his illustrated novels before the public while also establishing ATYR as a purveyor of major fiction and a magazine that would eventually rival the Cornhill.

Thanks so much, Pete, for posting these. I was wondering if the adverts in AYR signify the ways in which Dickens was exploiting his ‘brand’. Perhaps, for some readers with spare cash, the monthly issues represented a collectible commodity. I am somewhat reminded of modern technology companies like Apple or Nintendo releasing ‘new’ versions of their best-selling products with only minor – sometimes minuscule! – changes or upgrades which appeal to a hardcore of dedicated fans with disposable income.

However, as Joanne observes, Dickens was also ever keen to keep his public persona and his work before the public, which must have been an important motivating factor for these (commercially unsuccessful) monthly parts.

I have just been re-reading Laurel Brake’s wonderful paper from the Dickens Journals Online conference back in March and she makes some fascinating observations about this issue. Firstly, she remarks that the weekly and monthly magazine format ‘kept Dickens, week after week, visible and in contact with his readers. For the last two decades of his life, they might be viewed as the economic and material base on which his other and various activities were built’. In relation to the monthly format, she observes that the wrappers allowed advertising space, which generated extra revenue, and, also, they were cheaper and easier to ship abroad, thus making them a vital means for Dickens to reach his worldwide audience. Laurel is talking about the monthly parts of AYR, but I wonder if some of her observations could also be applied to the monthly parts of TOTC?

Thanks for posting Laurel’s insights, Ben. Perhaps unsurprising to see money as a deciding factor (even though it didn’t work out as successfully as planned). Out of interest, do we know if Dickens repeated the experiment with Great Expectations? And if he did decide to publish it in monthly instalments in addition to the weekly appearances in ATYR, was it any more successful than the ATOTC monthlys?

Interestingly, Dickens didn’t repeat the experiment with Great Expectations, publishing it in weekly parts in AYR from 1 December 1860 to 3 August 1861, with a standard 3-volume edition, published by Chapman and Hall, following closely. Dickens did start writing the novel as a monthly serial, to be published outside of his journal, but the relative failure of Charles Lever’s ‘A Day’s Ride’ (which we’re fond of in the DJO office, primarily because it’s bonkers) forced him to adapt his new novel to the same weekly format as TOTC. Lever’s picturesque serial was unceremoniously booted from the front page and replaced by GE. So, once again, economic motivation was foremost. Dickens’s also received the princely sum of £1,000 from Harper’s Weekly for the rights to US publication and the novel actually began publication in Harper’s a week earlier than in the UK — a neat reversal of the usual state of affairs.

The phiz illustrations are definitely not my favorite ones, although I do love the frontispiece “Under the Plane Tree”. I think Phiz may not have known what to do with this particular novel, so he almost “phones it in.” I think the Barnard illustrations are a lot more iconic, and I’m also very fond of the A A Dixon illustrations from the twenties.

I’m undecided on the illustrations at present. Obviously in execution they are lacking, (two weeks of watching the Olympics is having a subtle influence on my vocabulary, I notice) but the design of both is sound. The first illustration especially manages to capture the dynamics of the scene better to my eye than Barnard’s and Dixon’s. I guess what I’m saying is that these illustrations represent a great illustrator who is not working at his best – the ideas are still outstanding, but for whatever reason, he is no longer putting the effort in.