The first thing that strikes me about this opening section of the novel is the sheer busy-ness of it. Though we might at the end be swept up by questions of who has been recalled to life, who has been immured for 18 years, the opening chapters begin by provoking questions about state religion and superstition, international relations – between England and France, and England and America, and questions of the relations between past and present. They also produce, as do many of Dickens’s novels, a pervading sense of overwhelming violence, both in terms of the personal danger that attends the travellers on the mail coach, but also the state violence that, whether in Britain or in France, is meted out on the slightest pretext. Added to that is the really chilling sense of chapter 3’s opening lines about isolation, secrets and loneliness: ‘A solemn consideration, when I enter a great city by night, that every one of those darkly clustered houses encloses its own secret; that every room in every one of them encloses its own secret; that every beating heart in the hundreds of thousands of breasts there, is, in some of its imaginings, a secret to the heart nearest it! Something of the awfulness, even of Death itself, is referable to this.’ Suspending all knowledge of what’s to come, which I agree with Pete is a tricky business, it is this section of the opening part that has made the biggest impression on me so far, and has done much to create the feel of almost visceral discomfort and foreboding that the opening section creates.

It’s very jarring then to read on to WIlkie Collins’s piece on credulous believers in advertisements, which is the next piece in All the Year Round, and which opens with the words: ‘I HAVE much pleasure in announcing myself as the happiest man alive.’ Does anyone have any thoughts about this juxtaposition?

I think you may have just set up a competition for the succeeding weeks to find the most jarring juxtaposition! Although I agree, going from buried alive to the happiest man alive is going to take some beating…

Pardon the fangirl moment, but are you the Pete Orford who’s doing the “Charles Dickens on . . .” series? I’m really enjoying those!

Thanks Gina. Although to be fair, it’s Dickens who does most of the writing!

As someone who always reads books sequentially, this episodic approach is much more familiar as a televisual experience. (And yes, I have dozed off before the closing credits only to waken in a completely different programme, so the “happiest man alive” jolt is not unfamilar either!)

The atmosphere conveyed by the writing of both the times and the specific scene is echoed in the high production values of the best of TV, while the cliff-hanger produces the same feelings of excitement mixed with frustration. At the moment, however, 31 weeks feels rather protracted (more like a US series rather than a UK one).

One the subject of jarring notes, I was most startled by the description of Jerry’s spiky hair. While the whole piece contains a lot of wry humour, Jerry’s shunning by leapfroggers seems uncharacteristically surreal. (To torture my TV simile even further, it’s like Getting On with a walk-on part by Noel Fielding.)

I too am taken upon this re-reading of the novel by the sense of foreboding that seeps throughout all three of these first chapters. What I find most interesting is Dickens’ use of the supernatural here, something that I hadn’t noticed in reading ATOTC before, perhaps because I didn’t just stop after the third chapter. In chapter one Dickens talks about spirit “rappings,” (which, I gather, was a big fad of the time) and messages from the spiritual realm. Chapter two is all about sinister messages, as Jarvis Lorry is actually riding ON the mail coach and receives/delivers a most cryptic message from and to Jerry. Chapter three has that creepy opening Gail mentioned where we are given the sense that everyone has an awful, secret message in their own hearts. All of these messages that Dickens gives us are very sinister: the impending American and French Revolutions which were most violent, the fierce times which lead travelers to be weary of having their throats cut, and finally, this illusive man who has been buried “alive” for eighteen years, and who apparently is to be the recipient of a message from Jarvis. Not to mention the fog that is everywhere here…needless to say, Dickens has me convinced that I would NOT like to be in Jarvis’ place.

Just want to say that I love that you’re doing this reread. ATOTC is my favorite novel. I’m really looking forward to more!

With a mention of Cock-lane and Joanna Southcott I don’t think the juxtaposition was accidental especially as in the next piece under the heading FOUND we find this:-

“ALWAYS An immense flock of gulls to believe in preposterous advertisements.”

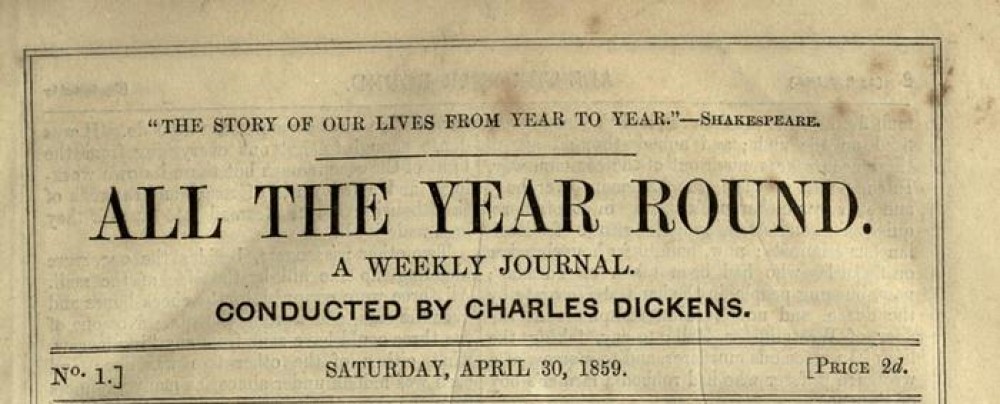

Another aspect of the opening that I don’t think has been discussed yet is that this isn’t just the opening of ATOTC, but of All the Year Round. Not only does Dickens omit a preliminary word such as he provided for Household Words, but he then provides instead this opening which, I think all bloggers have agreed, is ripe with mystery, open-endedness and uncertainty.

True, the lack of a specific introduction to the journal perhaps identifies ATYR more as a continuation of HW rather than a brand new journal (“brand” being the key word, as the presence of Dickens’s name at the top would encourage readers of HW to move over to his new project); nonetheless for the reader to dive straight in to ATOTC instead makes its early ambiguity all the more provoking.

I agree that the sudden appearance of the advertisement was a shock, especially as I initially thought it was a continuation of the story. I know Dickens does light and shade well but this was (I believed) taking it to the extreme!

Glad it wasn’t just me who read on, unwittingly for a little while thinking it was part of the story…

Catching up! It is so difficult to read as a ‘new reader’; however it is a long time since I read this book. Such colossal contrasts, with a duality of extremes established at the outset (best/worst, belief/incredulity) and clear pointers (trees and carts) to the French Revolution as the setting for the story. Mystery, darkness, violence, lawlessness, religion brutal, past and future intermingled, the rattling uneasy present. All is difficult, troubled, disturbed, fearful. Ever present danger in the dark. The horrifying nightmare, which we intuit will become real in some way, the softer touch of ‘her’. All this leavened by humour, as in the Dover mail paragraph in Ch.II. and lightened at last by the appearance of the sun, lighting up beautiful countryside with daylight at last. And a mysterious message, that well-known novelistic teaser! But this message has a deeper mystery than standard – how can the dead be recalled to life? And would they want to be?

If I’d been a Victorian reader, reading this as a first instalment, I don’t know how I could have put up with having to wait for the next chapter.

I find I read more slowly and carefully by being limited to instalments, and appreciate the genius of Dickens the better for that. This is just AMAZING stuff.

If you havent already seen it, you might like to take a look at the original manuscript of the novel too. It’s held by the V&A and is available online at:

http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/c/charles-dickens-a-tale-of-two-cities/

The page-turning software requires Flash, but you can browse through the entire manuscript. It’s quite difficult to read, but it gives a sense of how the novelist revised the text as he went along. We’ve also digitised The Mystery of Edwin Drood, and much of David Copperfield.

Douglas Dodds, Victoria and Albert Museum